People in Britain ask why the Irish are such vocal supporters of the Palestinians. In this Long Read Brian Críostoir explains the bonds of solidarity between our two peoples run deep.

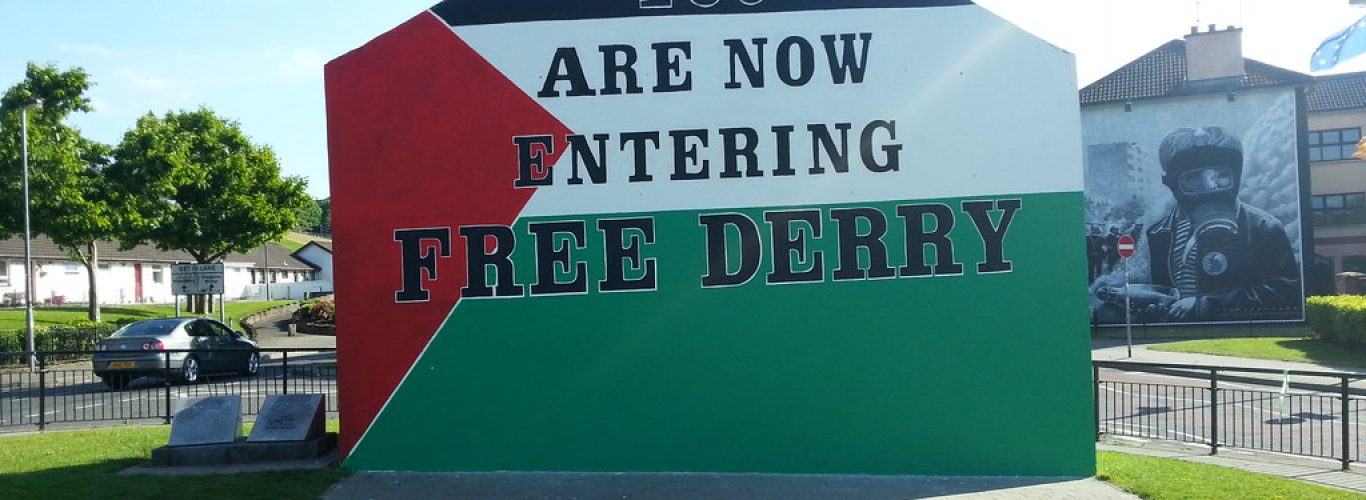

It’s August 2006. Israel’s ‘bunker-busting’ bombs are raining down on Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon, while their tanks smashed into Gaza. Veteran Civil Rights activist Eamonn McCann sits handcuffed in the back of a Land Rover, at Derry’s Strand Road police station. He and 8 others who came to be known as the ‘Raytheon 9’ have been arrested, accused of £350 000 of damage to the Raytheon facility in Springtown. Their aim was to thwart the making of murderous weaponry. McCann said “They came in riot gear and surrounded us in the room. We were playing cards at the time. We were arrested for burglary and criminal damage.”

This protest was just one of many that happened before and since. But the event is celebrated as one of the greatest triumphs of practical solidarity: Raytheon left Derry a few years later and it was seen as nothing less than total victory by the anti-war movement and a vindication of the action. The activists had faced a two year wait, with the threat of lengthy jail sentences hanging over them, before being acquitted by a jury who recognised that preventing war crimes was a justifiable defence for damaging property.

One activist, when visiting the refugee camps that were bombed said the decommissioning of Raytheon was ‘the best thing I ever did’.

To understand why feelings towards Palestine are so strong, we need to look at some history and the connections that have formed over time between our two movements: the campaign for Irish independence and unity and the struggle for liberation and justice for Palestine.

So far the Irish government has failed to reflect this feeling in its foreign policy. It raises what Richard Boyd Barrett called “words of concern, but no action” and the Israeli ambassador was recently invited to the Fiánna Fail Ard Fheis, in a bizarre move. The support for Palestinian liberation, ignored by the elite, is expressed by tens of thousands of people, on the streets.

David and Goliath

Ireland’s relationship with Palestine comes overwhelmingly from the grass roots. It’s possible to trace historical reasons all the way back to mandatory Palestine after the First World War, but a key turning point in the global imagination of Palestine occurred during the first or ‘stone intifada’ which exploded after the deliberate killing of refugees by an Israeli bulldozer in Jabalia Refugee Camp in 1987. Much of that camp was destroyed last week with over 400 civilians murdered.

The intifada was a social earthquake. Young people had endured a brutal 20 year occupation and wanted change.

Such sentiments chimed with people in Ireland who had known occupation themselves.The images that went around the world were iconic; small children with slingshots and stones, fighting huge tanks and armoured personnel carriers, petrol bombs being exchanged for tear gas and then live fire, crowds of protestors facing indiscriminate shooting. There were curfews, raids, endless checkpoints, humiliation, searches, internment without trial and torture. The brunt of the violence was taken by children, who, like today, were Israel’s fiercest enemies and easiest targets. Youths were shot, beaten and harassed. In response they built barricades with rubble, burning tires and hijacked cars. When raids occurred they beat bin lids against the concrete to warn their neighbours. They then played ‘cat and mouse’ with Israeli forces to draw them away from their intended targets, often suffering brutal or fatal consequences.

It is easy to see how these events struck a chord with people in Ireland.

Our collective experience and memories mirror much of the Palestinian experience. These events coincided with the aftermath of the Hunger Strike, when Irish republicans were building a mass movement of political action, sometimes in support of, but often independent from, the armed struggle.

The Oslo Accords in 1994, seen as an end to the intifada, no doubt gave President Clinton a sense of his own messianic importance, meaning he could turn his hand to ‘settling’ the conflict in Ireland, too.

The failure of Oslo occurred for exactly the same reason that purported solutions in Ireland stalled, too. They did not address the fact that the polities (Israel and ‘Northern Ireland’) had been built precisely to disenfranchise and segregate. Israel’s narrative, that it is under siege from all sides by hostile enemies, belies its overwhelming military superiority, as well as the fact that the state itself constantly reinforces that siege mentality for its own interests. It led to greater separation and a system of apartheid, of different rights for different groups. This has created in Palestine, in a few decades, what was enforced in Ireland for centuries.

In the weeks since 7th October 2023, Palestinian ghettos have shrunk even further, with rapid expulsions of families who are forced to stand at their front gate and watch Israeli fundamentalists laden with rucksacks walk into their house and claim it as their own.

The Second Intifada (200-2005) was prompted by a visit by Ariel Sharon to the Temple Mount in what was seen as a declaration of Israeli sovereignty over the beating-heart of Palestinian cultural life. The response was inevitable. American foreign policy had shifted from a Cold War footing towards the expansion of US military power in the Middle East and the brake cables on Israel were cut. Palestinian casualties soared. Increasingly, around the world, there was an integration of anti-war and Palestine solidarity struggles.

Solidarity in Action

In Ireland, those years were formative for a new generation of activists. The US was sending envoys to Ireland, championing dialogue, peace and reconciliation, while bombing Afghanistan. In 2003 US warplanes began refuelling at Shannon Airport while en route to an illegal war in Iraq. 2000 Protestors took part in a demonstration, many trying to directly occupy the runway.

When I asked Palestinians at the time what we could do to help their ‘situation’, as they call it, the most common answer was ‘do things that are visible from Palestine’. Other activists in Derry had heard the same call and the tremendous occupation of Raytheon was their response.

Internment and Hunger Strikes

The struggles have also been entwined by the shared experience of Irish and Palestinian prisoners. There are over 5000 Palestinian political prisoners, the highest number for 30 years. About a thousand are held in ‘administrative detention’, known to us by another name: internment. Over 1400 Palestinians have been effectively taken hostage since 7th October when Hamas launched its latest response to the occupation.

One in every 5 Palestinian men have been to prison in Israel, often for minor infractions of one of the 1600 rules imposed by the military occupation. Administrative detention found its way into Israeli legal thinking via the British Mandate and was revived in 2002, when prisoners were to be treated like criminals and so denied their prisoner of war status, much like the prisoners of Long Kesh. As such, Palestinian activists like the celebrated leader Marwan Barghouti, identified with the republican prisoners and Bobby Sands in particular. A message of their support was smuggled out of Nafha prison:

“We salute the heroic struggle of Bobby Sands and his comrades, for they have sacrificed the most valuable possession of any human being. They gave their lives for freedom.”

The British Dimension

Finally, there is of course, the British dimension. Israel is, fundamentally, a British creation.

Britain ruled Palestine from the end of WW1 until the formation of the Israeli state in 1948. Arthur Balfour, who was the architect of British support for an Israeli state, had cut his teeth as Chief Secretary in Ireland, where he ruthlessly suppressed Irish nationalism and defended the Mitchelstown Massacre by the Royal Irish Constabulary. When it came to the question of ridding the land of Palestine of its inhabitants, the British officer class, with experience of these tactics from Ireland to India, were only too keen to train the proto-Israeli militias in methods of terror. Ian Pappe, a leading Israeli historian explains:

‘Amatziyah Cohen, who took part in the operation, remembered the British sergeant who showed them how to use bayonets in attacking defenceless villagers; ‘I think you are all totally ignorant in your Ramat Yochanan [the training base for the Hagana] since you do not even know the elementary use of bayonets when attacking dirty arabs.’

The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, Ilan Pappe 2006 (pp 16)

This was not just a matter of coincidence either. These military leaders were long schooled in the British mission to shape the world in the interests of their masters in London. The first British governor of Jerusalem, Ronald Storrs saw Balfour’s Declaration promising zionists a Jewish homeland in Palestine as an effort to create “a ‘little loyal Jewish Ulster’ in a sea of potentially hostile Arabism”. Israel was to be a client state: an attack dog against pan-arabism and the wider left.

The parallels could hardly be more stark and the colonial project to seize more Palestinian land and level villages has been matched by a desire to utilise natural borders like the River Jordan and the Syrian Golan heights. More recently the massive ‘separation barrier’ actually confiscated water-rich resources in the underground aquifers and is testament to the fact that Israel’s intention has been to erase the possibility of Palestinian subsistence in their ancestral homeland. If they cannot be expelled, they must live only on the most barren land.

Read in this context, the call last month to move south in Gaza whilst bombing the same place bleakly echoes Irish history. It is an ongoing Israeli ‘Hell or Connacht’ command.

In response to this historic wrong, the Palestinians have tried every method of resistance, from outright warfare to the daily nonviolent action that takes place in areas of settlement building that have snatched ever greater parts of the West Bank. A few years ago an attempt was made by grassroots activists to challenge the incarceration of Gaza through a mass march of ‘return’ by refugees. They cited their inspiration from the Civil RIghts marches of the US and Ireland in the 1960s. The result was that Palestinians were cut down by sniper fire.

In the Great March of Return, 214 Palestinians and one Israeli soldier were killed. Over 36 000 Palestinians including over 8000 children were injured, often with what Amnesty International described as ‘hunting ammunition” and “high-velocity military weapons designed to cause maximum harm to Palestinian protesters who do not pose an imminent threat to them”. The UN called it ‘crimes against humanity’. You can see the full report here. Reading it can only throw up bitter memories of Bloody Sunday and the Ballymurphy Massacre.

Our Task

The Palestinians have no capacity to mount a defensive war against Israel, as illustrated by over 12 000 casualties in such a short time. But the occupation of the West Bank and the siege of Gaza, with tacit acceptance by Palestine’s neighbours, has crushed the possibility of meaningful political developments inside Palestinian society, too. This means that there are very few routes to any democratic, secular politics in Palestine, at present, let alone an independent state.

The only solution to that problem is international solidarity. Israel holds all the territory, all the firepower and the assistance of western military giants. It can only be denied legitimacy through actions of solidarity from those who are witness to the awful destruction of Palestine. And the movement is growing, indeed faster in many other countries than in Ireland.

We must build on our traditions of friendship and solidarity. Expel the ambassador, call for an immediate ceasefire and negotiations, a release of all political prisoners and a referral of Israel to the international Court of Justice. We must also take action to demonstrate to the people of Palestine that we are witness to the crimes committed against them and will act to stop the killing.

“We are all Palestinians, in our thousands and our millions”

People in Britain ask why the Irish are such vocal supporters of the Palestinians. In this Long Read Brian Críostoir explains the bonds of solidarity between our two peoples run deep.

It’s August 2006. Israel’s ‘bunker-busting’ bombs are raining down on Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon, while their tanks smashed into Gaza. Veteran Civil Rights activist Eamonn McCann sits handcuffed in the back of a Land Rover, at Derry’s Strand Road police station. He and 8 others who came to be known as the ‘Raytheon 9’ have been arrested, accused of £350 000 of damage to the Raytheon facility in Springtown. Their aim was to thwart the making of murderous weaponry. McCann said “They came in riot gear and surrounded us in the room. We were playing cards at the time. We were arrested for burglary and criminal damage.”

This protest was just one of many that happened before and since. But the event is celebrated as one of the greatest triumphs of practical solidarity: Raytheon left Derry a few years later and it was seen as nothing less than total victory by the anti-war movement and a vindication of the action. The activists had faced a two year wait, with the threat of lengthy jail sentences hanging over them, before being acquitted by a jury who recognised that preventing war crimes was a justifiable defence for damaging property.

One activist, when visiting the refugee camps that were bombed said the decommissioning of Raytheon was ‘the best thing I ever did’.

To understand why feelings towards Palestine are so strong, we need to look at some history and the connections that have formed over time between our two movements: the campaign for Irish independence and unity and the struggle for liberation and justice for Palestine.

So far the Irish government has failed to reflect this feeling in its foreign policy. It raises what Richard Boyd Barrett called “words of concern, but no action” and the Israeli ambassador was recently invited to the Fiánna Fail Ard Fheis, in a bizarre move. The support for Palestinian liberation, ignored by the elite, is expressed by tens of thousands of people, on the streets.

David and Goliath

Ireland’s relationship with Palestine comes overwhelmingly from the grass roots. It’s possible to trace historical reasons all the way back to mandatory Palestine after the First World War, but a key turning point in the global imagination of Palestine occurred during the first or ‘stone intifada’ which exploded after the deliberate killing of refugees by an Israeli bulldozer in Jabalia Refugee Camp in 1987. Much of that camp was destroyed last week with over 400 civilians murdered.

The intifada was a social earthquake. Young people had endured a brutal 20 year occupation and wanted change.

Such sentiments chimed with people in Ireland who had known occupation themselves.The images that went around the world were iconic; small children with slingshots and stones, fighting huge tanks and armoured personnel carriers, petrol bombs being exchanged for tear gas and then live fire, crowds of protestors facing indiscriminate shooting. There were curfews, raids, endless checkpoints, humiliation, searches, internment without trial and torture. The brunt of the violence was taken by children, who, like today, were Israel’s fiercest enemies and easiest targets. Youths were shot, beaten and harassed. In response they built barricades with rubble, burning tires and hijacked cars. When raids occurred they beat bin lids against the concrete to warn their neighbours. They then played ‘cat and mouse’ with Israeli forces to draw them away from their intended targets, often suffering brutal or fatal consequences.

It is easy to see how these events struck a chord with people in Ireland.

Our collective experience and memories mirror much of the Palestinian experience. These events coincided with the aftermath of the Hunger Strike, when Irish republicans were building a mass movement of political action, sometimes in support of, but often independent from, the armed struggle.

The Oslo Accords in 1994, seen as an end to the intifada, no doubt gave President Clinton a sense of his own messianic importance, meaning he could turn his hand to ‘settling’ the conflict in Ireland, too.

The failure of Oslo occurred for exactly the same reason that purported solutions in Ireland stalled, too. They did not address the fact that the polities (Israel and ‘Northern Ireland’) had been built precisely to disenfranchise and segregate. Israel’s narrative, that it is under siege from all sides by hostile enemies, belies its overwhelming military superiority, as well as the fact that the state itself constantly reinforces that siege mentality for its own interests. It led to greater separation and a system of apartheid, of different rights for different groups. This has created in Palestine, in a few decades, what was enforced in Ireland for centuries.

In the weeks since 7th October 2023, Palestinian ghettos have shrunk even further, with rapid expulsions of families who are forced to stand at their front gate and watch Israeli fundamentalists laden with rucksacks walk into their house and claim it as their own.

The Second Intifada (200-2005) was prompted by a visit by Ariel Sharon to the Temple Mount in what was seen as a declaration of Israeli sovereignty over the beating-heart of Palestinian cultural life. The response was inevitable. American foreign policy had shifted from a Cold War footing towards the expansion of US military power in the Middle East and the brake cables on Israel were cut. Palestinian casualties soared. Increasingly, around the world, there was an integration of anti-war and Palestine solidarity struggles.

Solidarity in Action

In Ireland, those years were formative for a new generation of activists. The US was sending envoys to Ireland, championing dialogue, peace and reconciliation, while bombing Afghanistan. In 2003 US warplanes began refuelling at Shannon Airport while en route to an illegal war in Iraq. 2000 Protestors took part in a demonstration, many trying to directly occupy the runway.

When I asked Palestinians at the time what we could do to help their ‘situation’, as they call it, the most common answer was ‘do things that are visible from Palestine’. Other activists in Derry had heard the same call and the tremendous occupation of Raytheon was their response.

Internment and Hunger Strikes

The struggles have also been entwined by the shared experience of Irish and Palestinian prisoners. There are over 5000 Palestinian political prisoners, the highest number for 30 years. About a thousand are held in ‘administrative detention’, known to us by another name: internment. Over 1400 Palestinians have been effectively taken hostage since 7th October when Hamas launched its latest response to the occupation.

One in every 5 Palestinian men have been to prison in Israel, often for minor infractions of one of the 1600 rules imposed by the military occupation. Administrative detention found its way into Israeli legal thinking via the British Mandate and was revived in 2002, when prisoners were to be treated like criminals and so denied their prisoner of war status, much like the prisoners of Long Kesh. As such, Palestinian activists like the celebrated leader Marwan Barghouti, identified with the republican prisoners and Bobby Sands in particular. A message of their support was smuggled out of Nafha prison:

“We salute the heroic struggle of Bobby Sands and his comrades, for they have sacrificed the most valuable possession of any human being. They gave their lives for freedom.”

The British Dimension

Finally, there is of course, the British dimension. Israel is, fundamentally, a British creation.

Britain ruled Palestine from the end of WW1 until the formation of the Israeli state in 1948. Arthur Balfour, who was the architect of British support for an Israeli state, had cut his teeth as Chief Secretary in Ireland, where he ruthlessly suppressed Irish nationalism and defended the Mitchelstown Massacre by the Royal Irish Constabulary. When it came to the question of ridding the land of Palestine of its inhabitants, the British officer class, with experience of these tactics from Ireland to India, were only too keen to train the proto-Israeli militias in methods of terror. Ian Pappe, a leading Israeli historian explains:

This was not just a matter of coincidence either. These military leaders were long schooled in the British mission to shape the world in the interests of their masters in London. The first British governor of Jerusalem, Ronald Storrs saw Balfour’s Declaration promising zionists a Jewish homeland in Palestine as an effort to create “a ‘little loyal Jewish Ulster’ in a sea of potentially hostile Arabism”. Israel was to be a client state: an attack dog against pan-arabism and the wider left.

The parallels could hardly be more stark and the colonial project to seize more Palestinian land and level villages has been matched by a desire to utilise natural borders like the River Jordan and the Syrian Golan heights. More recently the massive ‘separation barrier’ actually confiscated water-rich resources in the underground aquifers and is testament to the fact that Israel’s intention has been to erase the possibility of Palestinian subsistence in their ancestral homeland. If they cannot be expelled, they must live only on the most barren land.

Read in this context, the call last month to move south in Gaza whilst bombing the same place bleakly echoes Irish history. It is an ongoing Israeli ‘Hell or Connacht’ command.

In response to this historic wrong, the Palestinians have tried every method of resistance, from outright warfare to the daily nonviolent action that takes place in areas of settlement building that have snatched ever greater parts of the West Bank. A few years ago an attempt was made by grassroots activists to challenge the incarceration of Gaza through a mass march of ‘return’ by refugees. They cited their inspiration from the Civil RIghts marches of the US and Ireland in the 1960s. The result was that Palestinians were cut down by sniper fire.

In the Great March of Return, 214 Palestinians and one Israeli soldier were killed. Over 36 000 Palestinians including over 8000 children were injured, often with what Amnesty International described as ‘hunting ammunition” and “high-velocity military weapons designed to cause maximum harm to Palestinian protesters who do not pose an imminent threat to them”. The UN called it ‘crimes against humanity’. You can see the full report here. Reading it can only throw up bitter memories of Bloody Sunday and the Ballymurphy Massacre.

Our Task

The Palestinians have no capacity to mount a defensive war against Israel, as illustrated by over 12 000 casualties in such a short time. But the occupation of the West Bank and the siege of Gaza, with tacit acceptance by Palestine’s neighbours, has crushed the possibility of meaningful political developments inside Palestinian society, too. This means that there are very few routes to any democratic, secular politics in Palestine, at present, let alone an independent state.

The only solution to that problem is international solidarity. Israel holds all the territory, all the firepower and the assistance of western military giants. It can only be denied legitimacy through actions of solidarity from those who are witness to the awful destruction of Palestine. And the movement is growing, indeed faster in many other countries than in Ireland.

We must build on our traditions of friendship and solidarity. Expel the ambassador, call for an immediate ceasefire and negotiations, a release of all political prisoners and a referral of Israel to the international Court of Justice. We must also take action to demonstrate to the people of Palestine that we are witness to the crimes committed against them and will act to stop the killing.

“We are all Palestinians, in our thousands and our millions”